Brain Development in Traumatized Children and Youth

A traumatic experience such as abuse or neglect can profoundly impact a child's brain development. Trauma may occur when a child feels intensely threatened by an event in which he or she is involved or witnesses, and it is often followed by serious injury or harm (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2005). A child may experience a single traumatic event or chronic trauma (occurring repeatedly over time). Other types of traumatic events include witnessing domestic or community violence; surviving a serious illness, war, or terrorism; or grieving the death of a loved one. A growing body of evidence documents that brain functioning is affected when a child experiences trauma and that cognitive, physical, emotional, social, health, and developmental problems can result.

A traumatic experience such as abuse or neglect can profoundly impact a child's brain development. Trauma may occur when a child feels intensely threatened by an event in which he or she is involved or witnesses, and it is often followed by serious injury or harm (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2005). A child may experience a single traumatic event or chronic trauma (occurring repeatedly over time). Other types of traumatic events include witnessing domestic or community violence; surviving a serious illness, war, or terrorism; or grieving the death of a loved one. A growing body of evidence documents that brain functioning is affected when a child experiences trauma and that cognitive, physical, emotional, social, health, and developmental problems can result.

Research overwhelmingly points to the benefits of supporting children and families at an early age to prevent maltreatment and its negative effects on brain development before they occur. In addition, cost-benefit analyses demonstrate the stronger return on investments that result from strengthening families, supporting development, and preventing maltreatment during childhood and adolescence rather than funding treatment programs later in life (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2007).

The Effects of Trauma on Children

No two children are affected by trauma in the same way. Depending on the age at which a child experienced a traumatic event or ongoing trauma, the initial response may range from hyperarousal (fight or flight) to dissociation (freeze and surrender), or a combination of the two (Perry, 2002). It is normal for children to process their feelings after a traumatic event. Common emotional responses include:

- Making sense of the event

- Creating memories

- Re-experiencing the trauma

- Avoiding reminders of the event

- Experiencing anxiety or sleep problems

- Acting impulsively (Perry, 2002)

Caregivers should not pressure the child to talk about the traumatic event but should be prepared to discuss it when the child is ready. Children who sense their caregiver is uncomfortable with or upset about the event may avoid talking about it. When the child begins talking, the caregiver should listen, avoid overreacting, answer questions, and provide comfort and support (Perry, 2002).

Children who continue to experience heightened emotional responses for longer than 1 month may be experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Perry, 2002).

Brain Development in Traumatized Children and Youth, Child Welfare Information Gateway August 2011, pp 2. For more information on Attachment and the benefits of a secure and stable relationship with a primary caregiver, see our Attachment page.

Read this article where Pediatrician Nadine Burke Harris describes how even with the unpredictability of stress in our world today, caregivers still play a vital role in mitigating toxic stress:

"Even in an atmosphere where stress is frequent and not controllable, a young child's parent or caregiver is the best shield against the effects of toxic stress. When a caregiver is able to help the child make sense of the world, manage difficult feelings and develop healthy coping skills, toxic stress can be prevented."

Caring for a Child Who Has Experienced Abuse or Neglect

“Children who have been abused or neglected need safe and nurturing relationships that address the effects of child maltreatment. If you are parenting a child who has been abused or neglected, you may have questions about your child’s experiences and the effects of those experiences.”

The publication linked below answers the following questions caregivers may have:

- What should I know about my child?

- What is child abuse and neglect?

- What are the effects of abuse and neglect?

- How can I help my child heal?

- Where can I find support?

- Resources

Parenting a Child Who Has Experienced Abuse or Neglect, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Child Welfare Information Gateway, December 2013, pp 1.

This is also a helpful and informative resource: American Academy of Pediatrics Guide to Helping Foster and Adoptive Families Cope with Trauma

Helping Young Children Heal Fact-Sheet

"Young children, toddlers, and preschoolers -- even babies -- know when bad things happen, and they remember what they have been through. After a scary event we often see changes in their behavior. They may cry more, become clingy and not want us to leave, have temper tantrums, hit others, have problems sleeping, become afraid of things that didn't bother them before, lose skills. Changes like these are a sign that they need help. Here are some ways you can help them.

Click here for this checklist of ways to help children heal from trauma."

Early Trauma Treatment Network Child Trauma Research Project University of California San Francisco, Chandra Ghosh Ippen, Alicia F. Lieberman, & Patrick Van Horn, 2005.

How to Help Your Children Cope with Trauma

- Indicate you are available to listen to the child

- Use a calm tone of voice

- Get on the child's level - stoop or sit on the floor

- Reassure children that they will be safe

- Don't minimize the child's feelings, don't say "Stop being a baby, don't cry"

- Follow the child's lead:

- If the child wants to talk, listen

- If the child wants to be held or picked up, do so

- If the child is clingy, be patient

- Allow children to show their fears; give support

- Help children identify their feelings

Helping Young Children Cope and Families Cope with Trauma, Harris Center for Infant Mental Health Violence Intervention Program & Safe Start Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans.

Complex Trauma: Facts for Caregivers

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) Complex Trauma Collaborative Group has developed this new fact-sheet designed specifically for caregivers, which provides information on how a caregiver can support a child with a complex trauma history. It presents information that can help a caregiver understand complex trauma and recognize the signs and symptoms of complex trauma in their child. It also offers recommendations for what the caregiver can do to help their child heal, as well as tips for self care.

June 2014 Fact-Sheet.

Enhancing [Caregiver]-Child Interactions.

Research shows that babies prefer human interaction more than anything else (ZERO TO THREE, 2008). The connections babies form with their caregivers and the experiences they share are essential to promoting healthy brain development. Because many parents worry that they don't know how to support their baby's development, you can teach them basic parenting skills (touching, holding, comforting, rocking, singing, and talking to) and explain that these simple interactions are some of the best stimulation a baby can receive (ZERO TO THREE, 2008).Prepare caregivers to support child development and provide appropriate learning opportunities by describing the stages of child development and the timeline for milestones they can expect their children to achieve. Children build upon skills over time as they accomplish increasingly difficult and varied tasks (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2007). Caregivers should understand that children do not learn faster if they are forced to attempt activities they are not developmentally ready for yet. In addition, explain to caregivers of maltreated children the negative development outcomes that may result from maltreatment. Because the child's "developmental age may be younger than his or her chronological age, the caregiver should adjust expectations and modify learning activities to meet the child's developmental needs (Perry, 2006).

Supporting Brain Development in Traumatized Children and Youth, Child Welfare Information Gateway August 2011, pp 12-13.For more information on the ages and stages of child development, please see our Ages and Stages page. For more information for caregivers, see our Caregiver Information page.

Ages & Stages

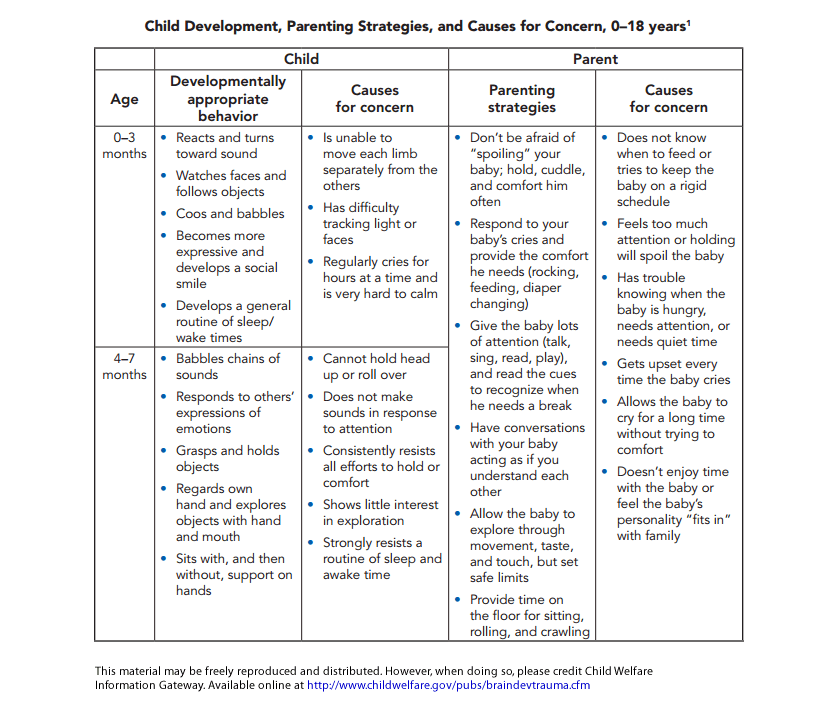

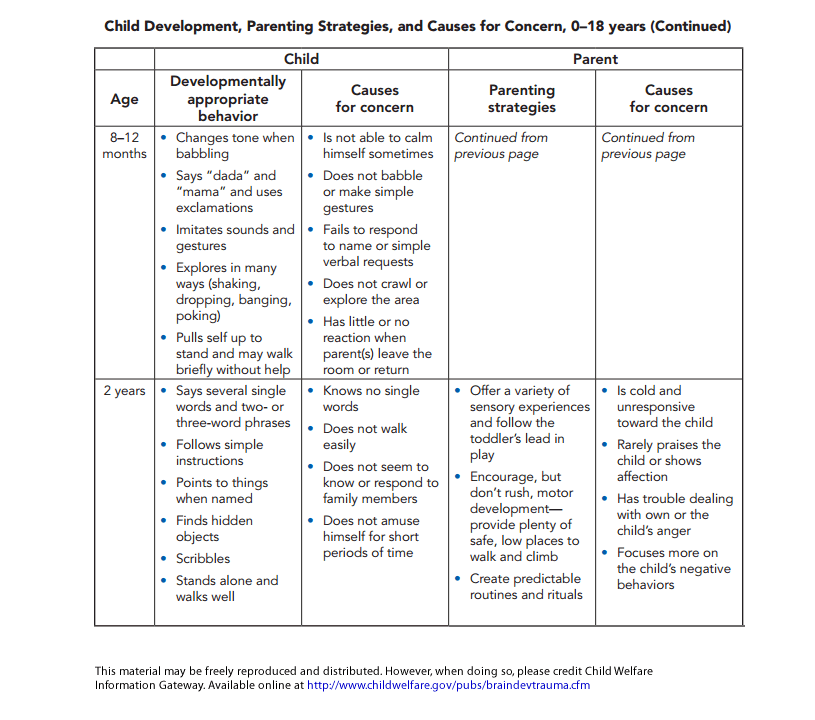

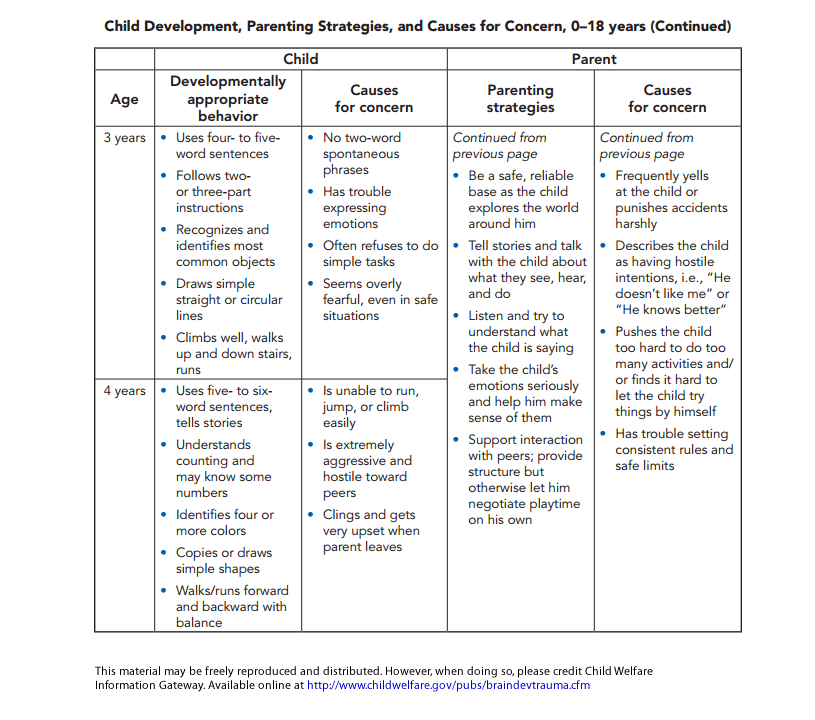

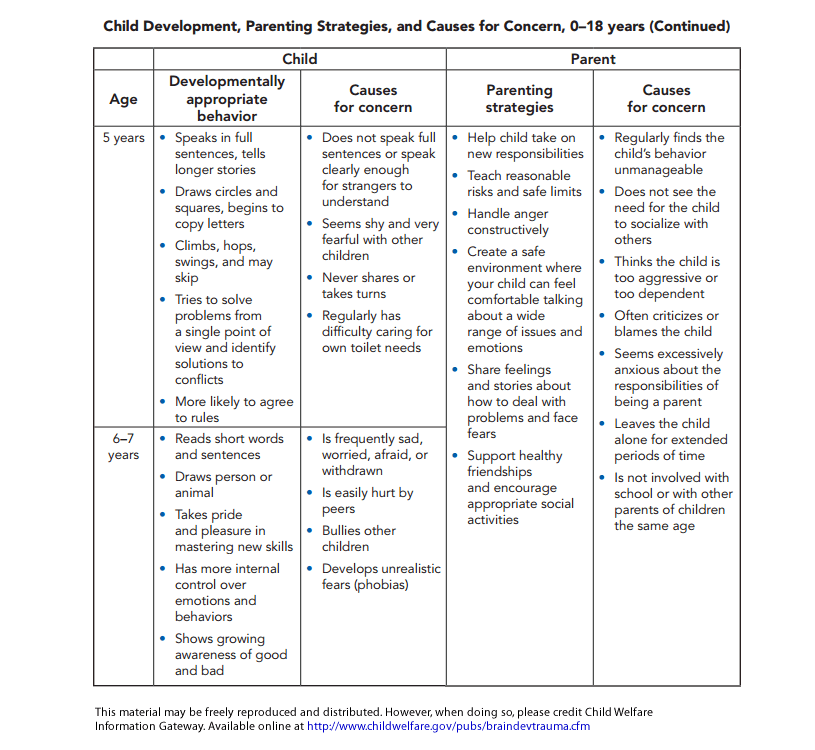

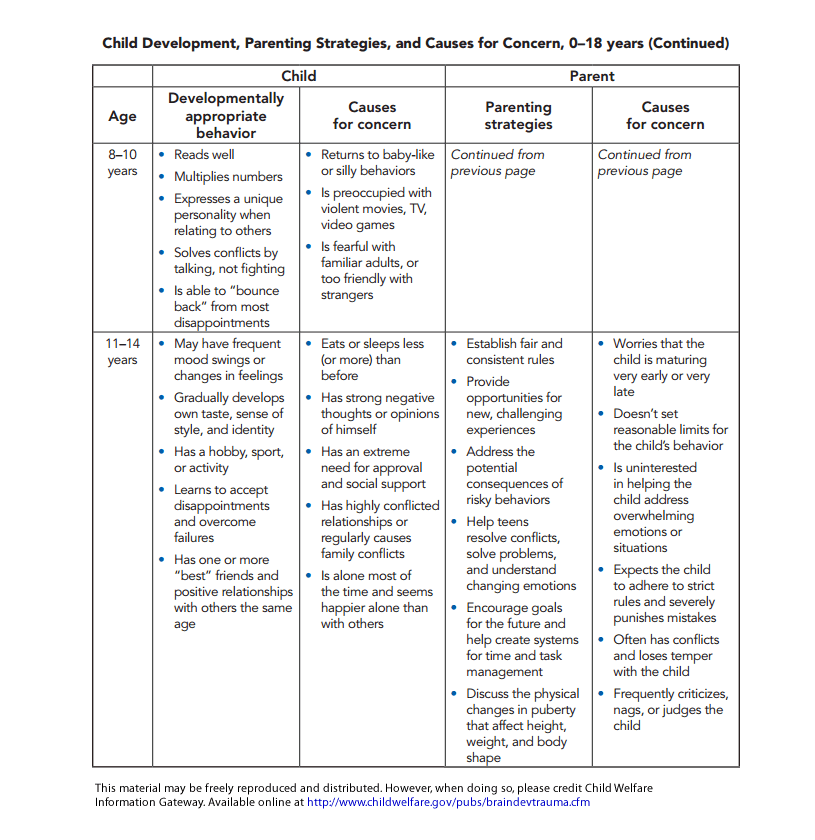

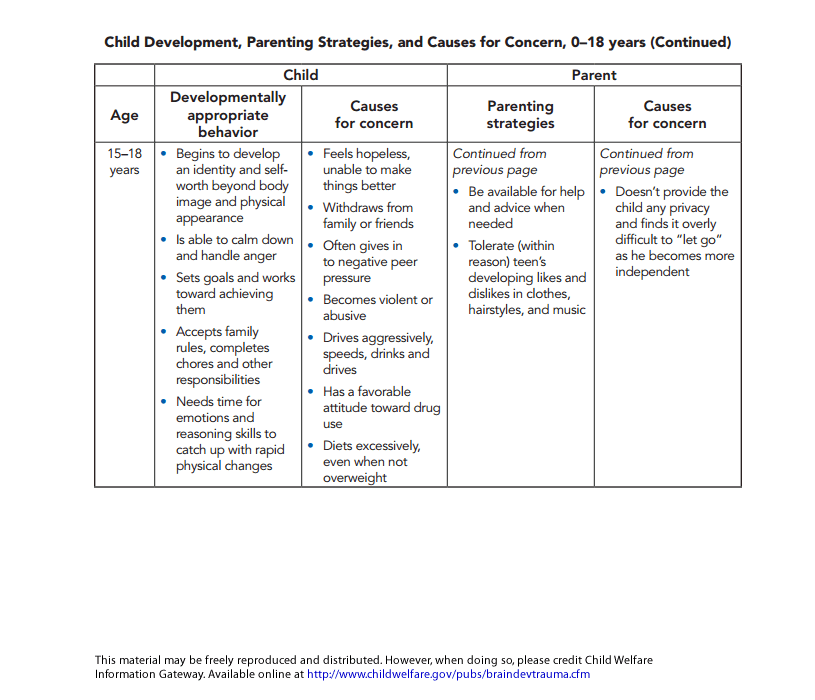

Below are a series of ages and stages charts that describe developmentally appropriate behavior and causes for concern for various ages.

“There are sensitive periods for developing certain abilities (such as when infants form attachments with their parents) that, if unachieved, could impair later development. Every child grows at his or her own pace, but most children achieve developmental milestones within the same general timeline. Keep in mind that the impact of abuse or neglect may cause children to develop at a slower rate (Perry, 2006) and that children born prematurely may also achieve milestones at different times, depending on the degree of prematurity. The chart [in this publication] provides general guidance on developmentally appropriate behavior in children, behaviors of the child or parent that may be a cause for concern, and positive parenting strategies. You may want to adjust your expectations according to the child’s needs and the parent’s situation.“

Source: Supporting Brain Development in Traumatized Children and Youth

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Child Welfare Information Gateway, August 2011.

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/braindevtrauma.pdf#page=5&view=Ages

Preparing and Supporting Caregivers Who Adopt

Foster parents who have been the child’s caregivers are the most important source of adoptive parents in the child welfare system. For the purpose of this section, “foster parents” means caregivers.

Benefits of [Current Caregiver] Adoption

Unlike most other types of adoption, children, youth, and foster parents involved in foster parent adoption have already spent time living as a family before the adoption is initiated and have had the opportunity to make some initial adjustments. In addition, research indicates that children waiting for adoption by their foster parents are less likely to experience disruption than children in nonrelative, non-foster-parent adoption (Berry & Barth, 1990; McRoy, 1999; Smith & Howard, 1991).

For children and youth, some of the other benefits include:

- A continuing and legally secure relationship with foster parents they know and trust

- An end to the uncertainty of foster care and, for many children, a positive psychological shift in their sense of identity, connection, and belonging (Triseliotis, 2003)

- The chance to remain in a familiar community, school, and neighborhood

- Tendency for shorter time to permanency than in other types of adoption (Howard & Smith, 2003)

- Greater likelihood of maintaining an ongoing connection with the birth family than in families formed through matching (Howard & Smith, 2003)

- Experienced parents to manage their needs (often including emotional and behavioral challenges due to trauma and complicated life histories)

- An established legal permanency for children and youth who would otherwise be wards of the court

For the adopting family, the advantages of adopting a child in their care include:

- Continuity of the relationship with the child or youth

- The opportunity to raise the child without oversight from an agency

- An established legal guardianship, becoming the sole decision-maker regarding school, religious practice, medical treatment, travel, discipline, and much more

- Often, both familiarity and a relationship with the child's birth family and greater knowledge of their child's background than in non-foster-parent adoption

- Access to continued support for the adoption of children with special needs, such as the adoption assistance subsidy

For the birth family, foster parent adoption sometimes means the birth parents know and can have a relationship with those who will be the permanent caregivers for their children. Foster parent adoptions are often open – an adoption arrangement in which identities are known and there is direct contact between birth families and adoptive families – either because a relationship developed between the birth and adoptive parents when the children were in care or because the children know their birth families' contact information and may contact them after adoption. More than one-third of all children who have been adopted (36 percent) had some postadoption contact with the birth families (Vandivere, Malm, & Radel, 2009).

Preparing and Supporting Foster Parents Who Adopt, Child Welfare Information Gateway January 2-13 pp.2-3.

For more information see our Trauma Informed Child Welfare Practice page.

Legal Disclaimer: Advokids provides educational information and resources to those who use our website, call our hotline, or submit requests for information via the website. Any information provided may not be construed as the giving of legal advice to any person about a particular legal matter and should not be relied upon as the basis for taking a particular action or refraining from taking a particular action in any legal matter. If you want or need legal advice about a particular legal matter, you should consult a lawyer.

5643 Paradise Drive, Suite 12B, Corte Madera, CA 94925 • 415.924.0587

11833 Mississippi Ave. 1st floor, Los Angeles, CA 90025

JOIN OUR EMAIL LIST • VISIT US ON FACEBOOK